Written by Paul Miron, Managing Director, Msquared Capital

For the first time since the GFC, the fragility of the global banking system has come into question as the 16th largest bank in the US collapsed, and one of Europe’s premier investment banks, Credit Suisse, sought rescue from the Swisse National Bank. How is it that a bank with a 166-year history, managing $1.6 trillion only a year ago,2 rapidly came crashing down?

In this month’s article, I wish to deconstruct and explore the interaction between interest rates and the events that led to a domino effect among the more modern US banks, as well as a couple of old giants. I will also explore the genuine risk posed to the Australian investor and the possibility of a global financial contagion.

The Beginning of Our Troubles – COVID-19

As a response to the emergency financial and health environment caused by COVID-19, central banks around the world dropped interest rates to an all-time low and provided generous fiscal programs to businesses on a scale we have not previously witnessed. Quantitative easing (‘QE’) was applied to buy existing bonds and provide market liquidity, whilst governments issued new Treasury Bonds to raise the much-needed capital for these emergency COVID-19 programs.

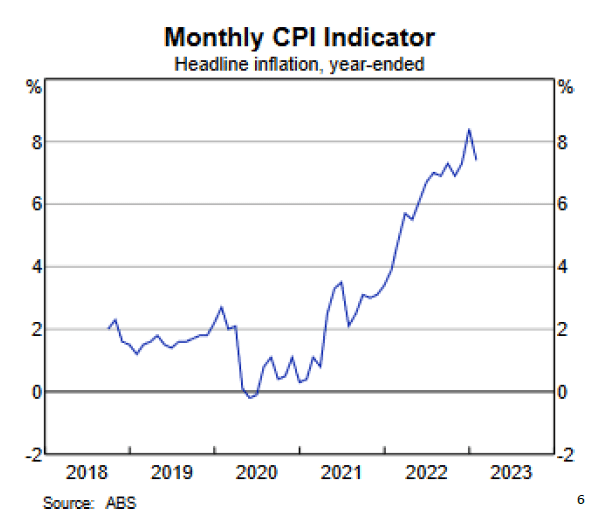

The sheer scale of this coordinated global economic response completely dwarfs the measures used by governments during the GFC (approximately 6.5x in size and scale across developed countries).3 In the aftermath, we Australians now find ourselves fighting the steepest inflation in over three decades.4 It is my belief that this period will be studied by economic historians with the tagline and conclusion – “Excess money supply equals high inflation” – affirming the late Milton Friedman’s own body of work into this subject matter.5

As the old saying goes – “There is no such thing as a free lunch”; we are certainly paying for it now. We are paying for dinner as well – WITH dessert.

Banks Buying up Treasury Bonds

The COVID-19 stimulus packages led to banks around the world seeing increased deposits. With the banks needing to invest this surplus money somewhere, and the lending environment not being favourable to them, the banks resorted to purchasing newly issued government bonds at near-zero coupon rates. Buying treasury bonds was encouraged by regulators and was seen as prudent practice given that the treasury bond is one of the least risky assets to hold on your balance sheet amid a financial crisis. This low risk is due to the government essentially being a guarantor of the capital – in other words, the government will give you back your money with certainty. Buying treasury bonds also has the benefit of meeting the capital adequacy requirement imposed by regulators.

It has surprised everyone that the economy recovered so rapidly, fueled by pent-up demand and surplus savings. Unfortunately, this fast-paced recovery unleashed inflation, leading to the fastest and most consecutive interest rate increases in Australia’s modern economic history.7

Now, let us shift our focus back to the so-called “risk-free” treasury bonds. Most government bonds have a fixed income stream linked to the official interest rates at the time of issue. As the official cash rate increases, these assets diminish in value. The S&P/ASX Australian Government Bond Index has shown a greater than 10% fall since August 2021, with some of individual bonds falling in value up to 20%8 If the income stream for a government bond is say, 1%, this would be less attractive than the current cash rate of 3.60%. Therefore, the face value (price) falls as the cash rate rises, allowing the bond to be traded with the appropriate numbers.

Despite this, government bonds are still safe and secure. The government’s sovereignty backs the income stream. It is easily traded in the money market and considered as good as liquid cash for banks, with regulators requiring significant exposure to these instruments as part of the credit creation function performed by banking institutions. For example, every dollar held in bonds, allows four dollars to be lent to borrowers.

To read Msquared Capital’s full piece on how rapid rate rises put banks in peril, please click on the button below:

2. What happened at Credit Suisse and how did it reach crisis point? | Reuters.

3. https://unctad.org/system/files/information-document/osg_2020-12-18_StimulusPackages_en.pdf.

4. https://tradingeconomics.com/australia/inflation-cpi.

5. The Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory (1970).

6. https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2023/pdf/sp-gov-2023-03-08.pdf.

Content provided by:

Disclaimer:

Msquared Capital Pty Ltd ACN 622 507 297, AFSL No. 520293 (Msquared) is the Trustee of Msquared Contributory Mortgage Income Fund.

The information contained on this website should be used as general information only. It does not take into account the particular circumstances, investment objectives and needs for investment of any investor, or purport to be comprehensive or constitute investment advice and should not be relied upon as such. You should consult a financial adviser to help you form your own opinion of the information, and on whether the information is suitable for your individual needs and aims as an investor. You should consult appropriate professional advisers on any legal, stamp duty, taxation and accounting implications of making an investment.

The information is believed to be accurate at the time of compilation and is provided by Msquared in good faith. Neither Msquared nor any other company in the Msquared Group, nor the directors and officers of Msquared make any representation or warranty as to the quality, accuracy, reliability, timeliness or completeness of material on this website. Except in so far as liability under any statute cannot be excluded, Msquared, its directors, employees and consultants do not accept any liability (whether arising in contract, tort, negligence or otherwise) for any error or omission in the material or for any loss or damage (whether direct, indirect, consequential or otherwise) suffered by the recipient of the information or any other person. The information on this website is subject to change, and the issuer is not responsible for providing updated information to any person. The information on this website is not intended to be and does not constitute a disclosure document as those terms are defined in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). It does not constitute an offer for the issue sale or purchase of any securities or any recommendation in relation to investing in any asset.

Investors should consider the Fund’s Constitution, Information Memorandum (IM) and relevant Loan Memorandum (disclosure documents) containing details of investment opportunities before making any decision to acquire, continue to hold or dispose of units in the Fund. You should particularly consider the Risks section of the Information Memorandum and relevant Loan Memorandum. Anyone wishing to invest in a Msquared Contributory Mortgage Income Fund will need to complete an Application Form. A copy of the IM and related Application Form may be obtained from our office via email request from [email protected].

Past performance is not indicative of future performance. No company in the Msquared Group guarantees the performance of any Msquared fund or the return of an investor’s capital or any specific rate of return. Investments in the Fund’s products are not bank deposits and are not government guaranteed. Total returns shown for Msquared Contributory Mortgage Income Fund have been calculated net of fees and any distribution forecasts are subject to risks outlined in the disclosure documents and distributions may vary in the future. All figures and amounts displayed in this email are in Australian dollars. All asset values are historical figures based on our most recent valuations.

The information found on this website may not be copied, reproduced, distributed or disseminated to any other person without the express prior approval of Msquared.